Our OpenStreetMap interview series continues with a chat with Christopher Beddow about OpenStreetMap in the US state of Montana. Chris is starting a regular OSM Montana meetup (link below).

1. Who are you and what do you do? What got you into OpenStreetMap?

I am Christopher Beddow, Solutions Engineer at Mapillary (and OSM user cbeddow). I help bridge computer vision data extracted from user-contributed imagery with GIS and mapping–essentially turning data from images into geospatial data on the map. I work a lot with OSM, as well as other consumers of map data, and am very fortunate that I get to travel far and wide both professionally and personally. I first started using OpenStreetMap when I was a masters student, studying GIS at University of Washington. My passion for OSM developed much later, as I have spent the bulk of 2016-2018 traveling to multiple countries while living and working rather nomadically (or at least sporadically). In Tbilisi, Georgia, one of my favorite cities, I found that there were really no great maps, from any provider, so I began to take note of POIs and tidy up building footprints. As I traveled around the world I also started adding POIs of places I ate, drank, or slept, especially if the hosts were very kind and I felt inclined to help put their business on the map. My first opportunity to connect with OSM communities came from a visit to Los Angeles, where I helped organize a trip to Santa Catalina Island to collect Mapillary images and OSM data. Later I became an occasional attendee or OSM Hungary, since I have been residing in Budapest on and off. I was able to visit many other Maptime and OSM groups while giving community workshops about Mapillary, which often ended with me learning just as much about OSM as I taught about Mapillary. Since then I’ve attended meetups and conferences all over the US, Europe, and even Tanzania and Zanzibar during FOSS4G to see what local communities look like. Mapillary is based in Sweden, and we’re a 100% distributed team, so I personally try to use that as motivation to see the world through the mapping lens. All these travel experiences made me really passionate about OpenStreetMap, as I realized there is a truly powerful global community that I’ve been fortunate enough to join. My biggest influences have certainly come from OSM or Maptime groups in Colorado, LA, Hungary, Milan, France, Lesotho, Portugal, and Japan–I wouldn’t have this inspiration without those communities and key people in them. There are really too many to count.

Here’s a picture of Chris at FOSS4G in Dar es Salaam:

2. What would you say is the current state of OSM and the OSM community in Montana? What made you decide now is the time to organize?

OSM is surprisingly well-crafted in Montana, in patches. One of my favorite examples is the town of Harlowton, which is on a less-used highway that I enjoy driving when crossing the state. Other places have poor detail, or at the least tend to be missing almost all POIs. I consider OSM very useful for driving, hiking, and other route-based activities in Montana but severely lacking for POIs.

The community is small and fragmented–I think there are many individual mappers out there who aren’t aware that there are others like them nearby. In other cases, OSMers in Montana are part of groups like Montana Association of GIS Professionals (MAGIP) or the Montana Geo Meetup, which means they don’t always get to be in a community where OSM is the focus, the reason people come together. After spending so much time as a guest in OSM communities around the world, and after seeing presentations at State of the Map and FOSS4G about the status of OSM communities in such a variety of countries, I decided that many of the lessons could be brought back home.

Recently I’ve spent many hours mapping my hometown and favorite regions of Montana. I bought the Montana Brewery Passport, which encourages tourism to local breweries, and visited over a dozen of them over the course of a week-long trip. I realized how few of them were on the map, and when editing the map got to examine many Montana cities where these microbreweries are located, seeing the OSM data quality (or lack thereof). Finally, I started browsing through changesets and lists of users, using tools like Meet Your Mappers and How Do You Contribute. I decided as result that Montana needs a forum for these users to share and collaborate, so I started a Meetup group for OpenStreetMap Montana and began messaging users with invitations. As I write these, we are up to around 9 or 10 members. Montana is a big state, and we can have a substantial impact on OSM here even as a small united group, while alone we are just chipping away at an impossible challenge.

3. What are the unique challenges and pleasures of OpenStreetMap in Montana? What aspects of the projects should the rest of the world be aware of?

Montana has a beautiful landscape, lots of open space, and no cities larger than about 115,000 people. This means mappers get a little experience with urban areas, but often without the headache that comes with something too big and complex. We also can map very interesting places, like the wilderness outside of Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, a plethora of hiking trails and campgrounds, ski resorts, geyser basins, hot springs, and more. If you’re an outdoors lover, then collecting OSM data in the field is an even better reason to download a great app like GoMap!! or Vespucci and be active. There’s also that dopamine rush of mapping things nobody has recorded before–arriving to a small, beautiful mountain town like Cooke City and adding 20 businesses, the tiny school house, and the thirty or so building footprints feels like a big accomplishment. There are many, many other towns like that which can be taken from poor data quality to excellent in just a few minutes. In addition, if you’re a Mapillary user like me then roadtrips get a little more interesting. Most Montanans don’t bat an eye at driving 3 or 5 hours for a weekend trip, because everything is so spread out–but now I captured tens of thousands of street-level images in a weekend, with at least one camera on my car at all times. I am almost always trying to take new and unknown routes to my destinations in order to get Mapillary coverage, but this also leads to me discovering more of the state and making pitstops to add gas stations, trailheads, and more to OSM as I pass by. Later, I sit down behind the computer and pick out important map information from my Mapillary images. There are only 1 million people in Montana, which is larger than all states except Alaska, Texas, and California. This means we have 0.00001% of us in the meetup group, and massive amount of the map to curate. One could say that we have plenty of excitement ahead of us!

The rest of the world should be aware that it’s certainly possible to contribute to Montana from a distance, the same as many mappers contribute remotely to projects in developing countries or disaster relief situations. Recently I messaged with OSM user lyx, who has made a lot of contributions here but lives in Germany. He told me:

“I’m mapping Montana because I found it beautiful every time I’ve been there, and beautyful places should have beautiful maps :-) As there are very few mappers in Montana, I’m doing what I can to help.”

I also received a message from user stevea, who works on the OSM Wiki for railroads in Montana and wanted to ask me to encourage local mappers to assist in improving and cleaning up the railroad routes here. This is great to know that such efforts as this will be noticed on the outside.

Some very important and interesting challenges are the concepts of rural mapping and indigenous mapping. These areas I’m especially reliant on outsides sources for, because places such as rural Africa and Asia have so many OSM successes we can learn from, while indigenous mapping efforts in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia also serves as great examples to follow. Montana has a rich history of native cultures, and engaging with tribal governments and communities today has potential to be very empowering for these communities. The rural areas of Montana often overlap with tribal lands, but regardless of who lives there the rural areas also can be very marginalized from the more urban centers, as well as the rest of the country and the world at large. Using OSM to encourage people in such communities to map what’s important to them, as well as allowing them rely on OSM data as authority when local government data is lacking, can really have a positive effect. There are also many sites of cultural or historical importance, such as Pictograph Caves State Park or Little Bighorn Battlefield, which need to be mapped in a way that correctly represents their significance. In the Pryor Mountains south of Billings, there are many important spiritual and cultural places such as buffalo jumps, vision quest sites, and petroglyph groups that are revered or sacred–learning about how other communities handle mapping of sensitive places like this can inform us how to proceed here. With so much living cultural as well as fading history, there’s an opportunity to preserve and promote these things using the map, and to serve as an example globally just as much as we learn from the global community.

The biggest challenge is that OSM in Montana is very poorly known, probably on the same level as it is in other less populated and developed parts of the world. We don’t have the volume of geo-minded people that a place like Seattle, Berlin, or Tokyo does. The enthusiasm in those places is easy to take for granted, and here it is an uphill battle to show people why OSM matters, and why they should take time to contribute. I want to spread awareness not just of editing the map, but of the fruits of the map in such apps as Pocket Earth, Maps.me, OsmAnd, and one of my favorites for planning a jog or a hike, OpenRouteService. Montanans have a very common strain of thought with people I’ve talked to in places like Kazakhstan and Georgia–they believe that Google Maps is the highest authority, and that if their business, or a road, or street view isn’t available via Google then they are powerless to change that. Locals in Montana need to be aware that people with poor access to technology, with language barriers, and in even more isolated corners of the world have been able to take ownership of local maps through OSM. They need to be aware that we can build a better map than the one that comes pre-loaded on our phones, and that it’s impact on tourism, business, and other causes is tangible across the globe.

4. What is the best way for people to get involved in the OSM Montana community?

The best way is to connect with other mappers, which I recommend doing by joining both OSM Montana and Montana Geo meetups. From there, communication is key–share what you’re working on, ask questions, be social. I also recommend that Slack users join the OSM US slack channel, and connect with the larger US community, as a representative of Montana. Knowing we are part of something larger is a great motivation. Finally, I hope that experienced mappers across Montana can eventually take leadership roles, and organize local mapathons. One is already scheduled for GIS Day on November 14th in the state capital of Helena, Montana. And finally, if you’re not big on edit the map, I recommend installing the Mapillary app and visiting shop.mapillary.com to get a free windshield or bike mount, so you can contribute images to help keep OSM data fresh.

Finally, if all else fails, just open up OSM iD editor and start mapping your neighborhood. Every bit of effort makes the difference!

5. What steps could the global OpenStreetMap community take to help support OSM in Montana? How could other communities help a new community like yours get started?

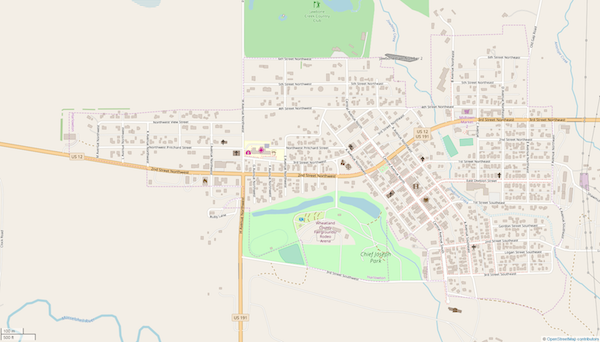

I hope more people around the world can step in and help us out here remotely, and I think it will kickstart the community as a result. In Billings, we have amazingly high quality satellite imagery from Digital Globe Premium layer when editing on OSM iD, better than I’ve seen in most places in the world. I have no idea why that’s the case, but I’ve been using it to trace buildings, sidewalks, crosswalks, even picnic benches and street lamps that are crystal clear from above. We also have a ton of Mapillary street-level imagery on all our highways, and in the downtown parts of most our largest cities, much of it contributed by me in my wandering escapades. Anyone can make use of this, from anywhere in the world. If we get the basics of the map up to speed from satellite and street-level imagery, it will make navigation and POI apps based on OSM a lot more relevant.

High map quality from Digital Globe Premium in downtown Billings, via OSM iD:

I recently took part of a Rural America meeting at State of the Map US, led by OSM user glassman. We talked about the very same challenges that Montana faces, especially in small towns and rural areas. In many of these cases, even Montana locals aren’t present in the most isolated parts of the map and must edit remotely. Once the map quality has been improved, I think efforts should be made by anybody who edits to contact local Chambers of Commerce, newspapers, and non-OSM community groups to let them know that their local map is up to date–and that they are free to help contribute. Many of these places, I hope, would be delighted to know that people around the world have an interest in putting them on the map, and that they don’t need to appeal to a corporate giant just to fix a road that was moved 5 years ago, or change the local bar to it’s newest name.

Other communities around the world can certainly help with remote mapping, and also can make sure to share knowledge–plans and agendas for mapathons can be reused, for example. I also think it would be great for OSMers to do some kind of exchange mapping, like have mappers in Milan spend an afternoon cleaning up Montana railways and tracing sidewalks, and Montana mappers can spend an afternoon learning to fix speed limits or trace buildings in the Italian Alps. It’s a fun way not only to learn about other parts of the world, but to understand the challenges that other communities face, as well as building a bigger bond between the international community. HOT OSM is a great way to do this for areas in humanitarian need, but we should also look at doing this to help out areas with low populations.

Overall, other communities around the world can help new communities get started by being the spark of inspiration and making an initial impact–show people how to map, and show them how mapping has an impact.

6. A few months ago OSM celebrated its 14th birthday, so we are well into the “teenager” stage of the project. But what will it look likes when it “grows up”? Where do you think the project will be in 10 years time, both globally and in Montana specifically?

I think that OSM will have a tough time finding its identity in the near future, because we have many bright people working on not just the map, but the backend, the tagging schemes, the use cases, and more. It’s very difficult to coordinate such a large global project, and also to find resolution among a multitude of good ideas that don’t always have room to coexist. I think right now there are many questions about the direction of OSM as far as the small details go, but this is different when we zoom out and take a high-level perspective. To me, it’s very clear that in 10 years OSM will become the authoritative map. It will be the map that always is most up to date, and the map that is owned by the public. I hope that young people who are technically minded will all recognize the name “OpenStreetMap”, because it’s always attributed in the corner of their mobile apps. I hope and believe that the mindset among all consumers of geospatial data will be “if it’s not on the map, then it doesn’t exist”–and that errors will be rapidly fixed. I think on a global scale we will see OSM as the one map that is continuous across borders, both in the quality of data and density of data.

I also believe that a massive amount of this data will be machine generated, but human verified. Whether mapping Montana or Mexico City, there are countless details that even a very determined group of human mappers doesn’t have the time, resources, or judgment to map. I believe that data extracted from satellite imagery, street-level imagery, and many other types of visual and non-visual sensors will represented most of what is added to the map on a daily basis in 10 years. I also think that almost all of this will be human verified in a very smooth and efficient workflow, or will be verified by a second layer of automatic QA that flags the data for human review before it can be added to the map. I think it’s clear that automation has its limitations today, but that it will only improve as the years go by. At the same time, community control of the map–human touch–is becoming more and more crucial, because voices around the world indicate that we as OSMers truly want to be involved in creating the map, not just in viewing the results. I believe that OSM will remain firmly in the hands of its dedicated users, while machine learning and simple automation will become more prevalent as we try to scale the amount of data that is collected by sensors and make sure it is cleaned, analyzed, and organized before we artfully integrate it into the global map. Finally, I believe that some maps will require far more detail, and far faster rates of refresh than humans are capable of supervising–in this case, high definition, machine-made maps will not replace OSM, but be built on top of OSM. OSM is made for humans and by humans, but also will be the basemap, the zoom 22 level that machine maps will use as a springboard when taking that zoom 100x times, maybe 1000x further.

In Montana specifically, we are sometimes far removed from the pace of technological advancement around the world. We won’t see autonomous vehicles, nor a need for HD maps, in our everyday lives on the same level that people in London, Dubai, or San Francisco might. For us, OSM will tailor to our needs. When machine mapping is needed, it won’t be done by us–it will be done by sensors, and we’ll be the ones who watch it happen, seeing the digital Montana change before the physical one changes. In 10 years, I believe that OSM in Montana will be powerful tool for learning, community building, and tourism. I think it will be a prime example of open and cutting edge software that young students will learn about, because unlike most software it offers the chance to see something very locally relevant–5th graders can see their playground on the map, its geometry, and how it’s classified. This is a gateway to understanding how databases work, what GPS is, what hex colors and CSS are, and many other technical terms that young students can learn hands-on with OSM. I also believe that communities will take pride in ensuring their gathering places on the map, such as churches and community centers, as well as important features like clinics, gas stations, and parks. It’s a symbol of having local control over the community’s digital presence. Finally, I think OSM will be very powerful for tourism–the National Parks in and around Montana are already a powerful draw for people worldwide, and I think that the nature we offer will become very important on the map. We can serve as a prime example of mapping not only cities, but rural and recreational areas that required detail mapping and local knowledge to ensure that tourism is safe, but also that visitors are informed about small businesses such as restaurants, lodging, and guide services who depend on tourism to survive. Many of these entities have yet to make a strong effort to put themselves on the internet much less the map, but in 10 years it will certainly be required not only for survival but certainly for flourishing. Overall, I think we’ll get the map up to date and more in Montana, and make it something that brings Montanans together.

Many thanks for the detailed response, Chris. Good luck to you and all the other Montana mappers. I hope your community thrives and serves as an example to OSM communities in rural areas around the world.

Please let us know if your community would like to be part of our interview series here on our blog. If you are or know of someone we should interview, please get in touch, we’re always looking to promote people doing interesting things with open geo data.