This year we’ll be expanding our regular blog interview series to focus not just on OpenStreetMap around the world and open geo data, but also people and projects using open data with a strong geographical component. A great example is the recently started OpenAQ project, which gathers open air quality data from around the world. We have the chance to speak with co-founders Christa Hasenkopf and Joe Flasher about the project.

1. What is OpenAQ and who is behind it?

OpenAQ is a community of scientists, software developers, journalists and others who care about air quality, building an open, real-time air pollution data hub that aggregates publicly available data from official monitors, standardizes them, and makes them easy to access through an open API.

As for who’s behind it, my husband Joe and I are. I’m an atmospheric scientist and I especially care about places that are polluted but understudied and under-monitored. Joe’s a software developer at Development Seed and loves open data, open-source projects.

For a couple of years, we lived and worked on air pollution issues in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, a city with severe air pollution. Through a short-term project with the National University of Mongolia, we saw the incredible power open data air quality work can have on the public. This path eventually led us to build OpenAQ.

2. Why have you started it, what are your goals with the project? What use cases do you see for the data?

Currently, there are approximately one million data-points published online daily from thousands of official air quality monitors worldwide. The entities that produce these data, often national-level environmental agencies, share it in varying forms providing differing ways for the public to access it, often not in ways that allow programmatic or historical access.

Several groups have begun to aggregate air quality data from these online sources over the past few years for a variety of purposes, like websites that share real-time air quality data, companies building air quality forecast models, and research studies. These groups are doing the awesome and intensive work of gathering these data before they can do cool stuff with them. No group makes the physical data publicly, programmatically, and historically available for free, nor their projects open-source. This means that if someone would like data to make a new app, build a visualization, do a cool new epidemiological study, or compare real-time data from other sources with a low-cost sensor, they’d have to replicate all of this work themselves or get data by manually requesting it from someone. And so, what happens in reality is that a lot of cool stuff that could be built never does.

OpenAQ is addressing this data access gap in order to let people build awesome stuff more easily. The data we aggregate is freely available through our API and built open-source. We provide a standardized base that others can build off of, whether that user is a developer in Jakarta making a real-time map or someone in Sao Paulo doing a multi-continent analysis. The other cool thing is, because the data are in a standardized format, open-source tools built off of OpenAQ will work universally. So, for example, a tool that sends out alerts for air quality violations on twitter for New York could also work easily for London.

3. Measuring air quality is great, but what can we actually do to improve it? Is it just a case that we hope showing that the air is bad will lead to government mandating change? Surely there is already immense evidence that bad air leads to bad health outcomes.

Here are reasons why we think measuring air pollution matters:

1: Measuring Progress - It’s definitely true that when air pollution reaches severe enough levels, you don’t need a monitor to tell you the air is bad. But if you want to do something about it, you need data to be able tell you what’s the severity of the problem, what plan might be most effective in tackling it, and if your plan is working or not. Like any big task, you’re probably not going to set realistic goals and achieve them if you don’t keep track of your progress and adjust accordingly along the way.

2: Providing Actionable Info to Public – The public is empowered to protect their own health when they have access to air quality data. Such data on its own or used to forecast levels can allow people to make personalized decisions based on their particular health and circumstances, like: where they want to live, what transportation they may take, or whether they’ll exercise outdoors, wear a mask, or turn on an air filter.

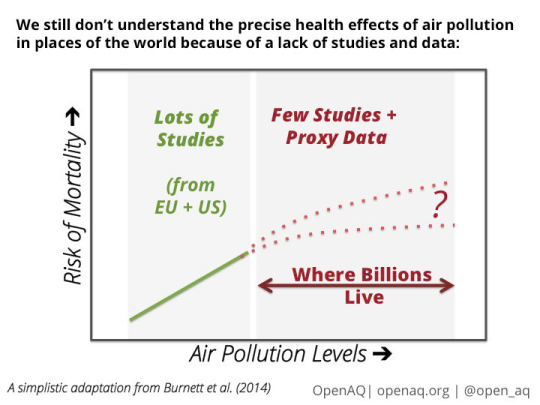

3: New Understanding – We do know air pollution is unhealthy for us, but surprisingly, we don’t have as great of an understanding of this at the most severe levels. Take PM2.5: most of the large epidemiological studies that have sought to understand the relationship between outdoor PM2.5 and mortality have been conducted in less polluted places of the world, like in the EU and US.

‘New understanding’ also encompasses ways to use air pollution data, coupled with other big, open data sources to understand its affects on daily life and mitigate them – or realize there are additional pressure points air pollution puts on society. If you’d like to read more on this topic, we recently published a post on Medium about it.

4. In the last few years we’ve seen a huge drop in barrier to entry for personal data collection, it’s now routine for people to know exactly where they travelled, how many steps they took, etc. But we know very little about the air we all breathe - especially for micro particles the devices used for measurement are complex - and expensive - machines. Are there any improvements in measurement devices that start to put data collection into the realm of the individual? Will we see a future in which we can each measure and analyze our personal exposure?

I think we are just on the verge – perhaps not quite on the scale of months, but rather in years – of seeing the proliferation of low-cost personal air quality sensors that give individuals a pretty accurate sense of their personal exposure. My personal opinion is that the inherent hardware technology of current low-cost sensors will not need to advance dramatically, but rather the field will find ways that networks of low-cost sensors ‘speaking to one another’ can be used to provide more accurate readings than any single instrument – so more advances on the software side of things. There are still other important questions that remain, like how to reduce user-related issues with low-cost individual sensor performance and even how to interpret or give health guidance for the typical very short term time resolution (e.g. on the scale of minutes or faster) that these sensors can measure air pollutants.

5. Recently the news has been full of stories about bad air quality, complete with apocalyptic photos of hazy megacities. Is this new, or just new coverage? How bad is it?

Air pollution is definitely not a new problem, but it is a pressing global one. The statistic that always gets me is that 1 out of every 8 deaths on the planet is due to air pollution, more than malaria and HIV/AIDS combined. These deaths are predominantly in developing countries, whereas air pollution issues in the EU and US – while still serious – have improved significantly over the last 50 years. I think there has been increased media coverage of air pollution issues as more places have access to real-time air quality data, and there is a better collective sense of similar issues people are facing locally around the world via information shared on international and social media. It seems you can often see how air pollution in one place stirs another citizens in another to say, “Hey, data are even worse here. Why aren’t we doing something?” At the same time, many, many places that may face significant air pollution issues still go unmonitored. For example, there are only a handful of online public air quality data sources for the entire continent of Africa.

6. How has the project developed so far? What has been the feedback?

When we started OpenAQ this past summer, it was just Joe and I in our living room in DC. We’d been talking about the need for this type of project for so long and unsuccessfully trying to convince others working on similar projects to open up their data to the public in the ways we thought would be most effective. We finally realized that if we wanted to see this happen, we should quit talking and get to work ourselves.

But we realized from the beginning that while we could start it off, it would take a community to really get it going and to sustain it. And the beauty of the open-source nature of the project is that it soon attracted help from all corners of the globe, from Development Seed, where Joe works here in DC to Spain to Mongolia.

Through funding from the Earth Journalism Network, we recently ran a workshop on the platform in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, and were blown away by the interest of the community and the visualizations and stories they’ve already created with the data.

To date, the platform has aggregated more than 2.8 million data points from 400+ locations in 13 countries. We plan to keep adding data sources and will continue to adapt the API and the standard format of the data according to feedback from the OpenAQ Community. We’re also working on building some simple data exploration and visualization tools for users to more easily access and ‘play’ with the data.

7. Any thoughts on how open data projects with a geographical element, like OpenAQ, can best collaborate and benefit from the open geo community, particularly the OpenStreetMap community?

In systems with a prominent geographic component, like OpenAQ, that geo component is generally incredibly key to the platform. The data we’re capturing for OpenAQ becomes so much more valuable if it is provided along with geo coordinates, that a large focus of ours should be on getting those coordinates. Unfortunately, not all sources we get the data from have this information available. OpenStreetMap has already organized local chapters globally and the ability to tap into that group for local knowledge of where the measurements stations will be incredibly helpful.

The OpenStreetMap community is also adept at taking data from an open project and using it in a myriad of ways. This is ideally what we’d like to happen with OpenAQ, and so we’d love to see what the community can build on top of the platform.

8. In closing, what are the best ways for readers to contribute to the OpenAQ project?

So many! From hearing about additional sources to giving advice on what would make our data format or API more useful to helping build data-fetching to holding an OpenAQ workshop, there really are so many ways to get involved.

Here’s a recent Medium post on some ideas for ways to get involved, and check out what the OpenAQ Community has already been building. Feel free to chat with us on Slack, view our source-code on GitHub or reach out at info@openaq.org.

And lastly, we’re planning on holding an OpenAQ meet-up on 10 Feb in Washington D.C. at Development Seed at 7pm. Anyone in the area is welcome to join. More info and the RSVP is here.

Many thanks Christa and Joe for chatting with us, and all the OpenAQ volunteers around the world for taking the lead on getting this critical data out there. It is hard to think of a topic more relevant to everyone globally than clean air. Hopefully this interview will draw some attention and more support to your efforts. I encourage all readers to get involved. You can follow the project on twitter at @Open_AQ.

You can see all the Open Geo interviews here. If you are or know of someone we should interview, please get in touch, we’re always looking to promote people doing interesting things with open geo data.